No one warned me that there was something else lurking within the cold. Hat, gloves and shoes or the cold would get me. Colleagues warned me of other things too. I had a car organised to meet me I’d been forewarned. I flew in, and we landed in the early afternoon. That first time, I was in Moscow on business. I stayed there, pressed up against the window, watching her body on the road until the cars around hid it from view. As my driver worked his beaten-up Volga past, I pressed my face and hands flat against the chill, mud- spattered glass. The woman, face down in the middle of the road, her legs spread wide as the cars drove around her. The old man struggling to rise from the snow that clutched him within its grasp, the stains on his trousers, slick with the sheen of ice. I knew it was more than that, but only after what I’d seen. Vodka and cold are a good explanation for the deaths on the city streets - a rational explanation. They say it’s the vodka and the cold, but I know better. I was warned about the cold before I got there. If something breaks, they leave it it’s cheaper to let dead things lie. They can’t get salt or sand, so they grit the roads with earth.

The New Russians have a practicality born of desperation in their new-found freedom. To get a new car costs less than trying to fix the old one. I asked my driver, and the explanation was simple. Snow lay piled high above the wrecks that people had simply abandoned by the side of the main highway to the city. The light was opalescent, milky with the haze that comes from cold, and the streets were paved with dirt.

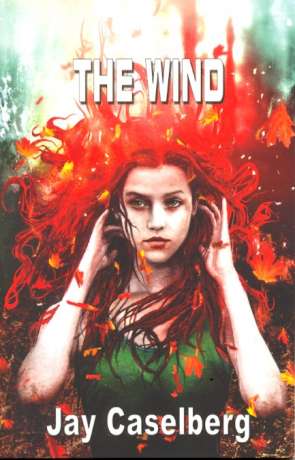

The first time I arrived in that chancre of a city, the sun shone. In the heart of the New Russia, in the middle of winter, there are many such risks. In every city there lies a risk, but if you treat the uncertainty dispassionately, with just a jot of sang-froid, then you survive. When you walk the streets of Moscow, though you may not know it, you walk among the dead. “The Dead of Winter” - illustration by Stjepan Lukac:

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)